Try Implementing a Small Reactivity System

Reactivity Mechanism Using Proxy

Differences in Design Compared to the Current vuejs/core

As of December 2024, Vue.js's Reactivity system employs a doubly linked list-based Observer Pattern.

This implementation, introduced in Refactor reactivity system to use version counting and doubly-linked list tracking, has contributed significantly to performance improvements.

However, for those implementing a reactivity system for the first time, this can be somewhat challenging to grasp. In this chapter, we will create a simplified implementation of the traditional (pre-optimization) system.

For a more detailed explanation of a system closer to the current implementation, please refer to Reactivity Optimization.

Another significant improvement, feat(reactivity): more efficient reactivity system, will be covered in a separate chapter.

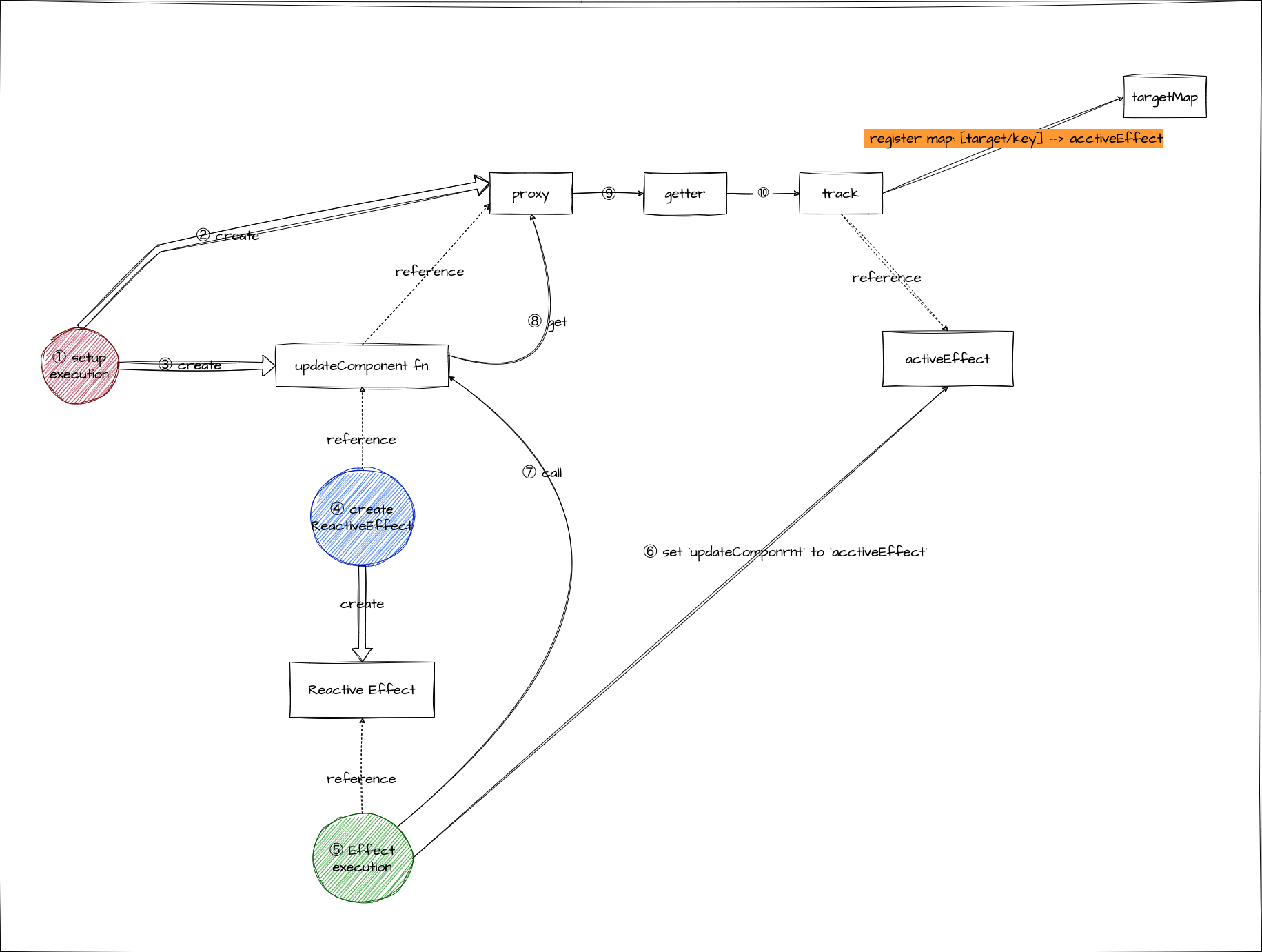

To clarify the purpose again, the purpose this time is to "execute updateComponent when the state is changed". Let me explain the implementation process using Proxy.

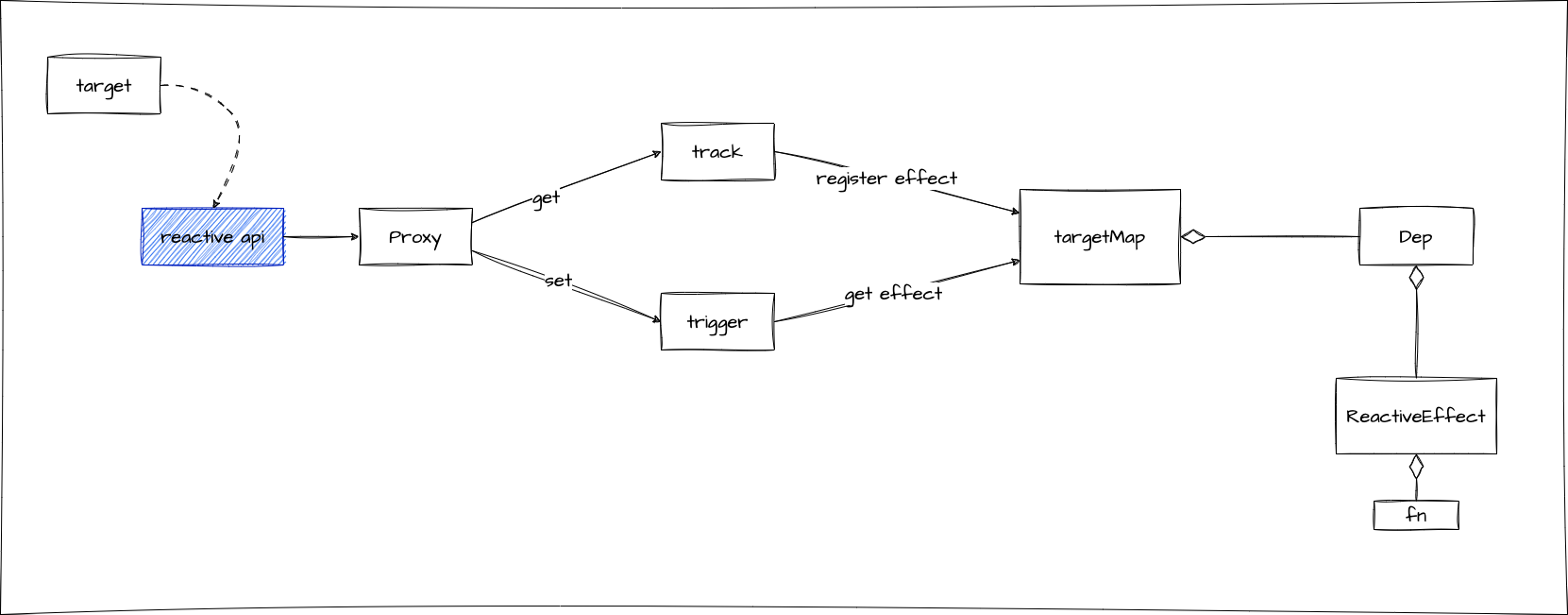

First, Vue.js's Reactivity System involves target, Proxy, ReactiveEffect, Dep, track, trigger, targetMap, and activeEffect (currently activeSub).

Many terms suddenly appeared, but don't panic!

If we look at each role one by one, the puzzle pieces will fit together.

First, let's aim to "roughly grasp the big picture".

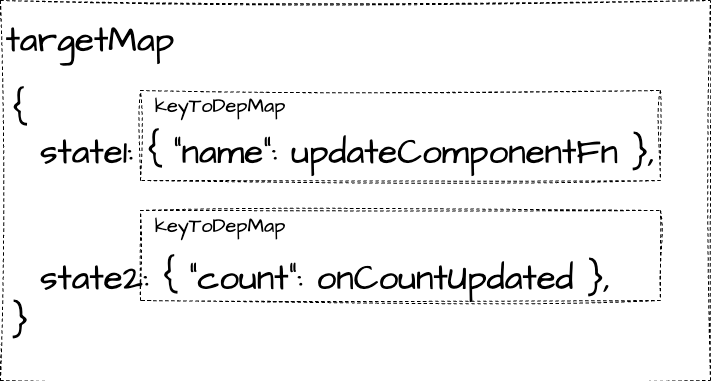

First, let's talk about the structure of targetMap. targetMap is a mapping of keys and deps for a certain target. Target refers to the object you want to make reactive, and dep refers to the effect (function) you want to execute. You can think of it that way. In code, it looks like this:

type Target = any // any target

type TargetKey = any // any key that the target has

const targetMap = new WeakMap<Target, KeyToDepMap>() // defined as a global variable in this module

type KeyToDepMap = Map<TargetKey, Dep> // a map of target's key and effect

type Dep = Set<ReactiveEffect> // dep has multiple ReactiveEffects

class ReactiveEffect {

constructor(

// here, you give the function you want to actually apply as an effect (in this case, updateComponent)

public fn: () => T,

) {}

}It means registering "a certain effect" for "a certain key" of "a certain target (object)".

It might be hard to understand just by looking at the code, so here is a concrete example and a supplementary diagram.

Consider a component like the following:

export default defineComponent({

setup() {

const state1 = reactive({ name: "John", age: 20 })

const state2 = reactive({ count: 0 })

function onCountUpdated() {

console.log("count updated")

}

watch(() => state2.count, onCountUpdated)

return () => h("p", {}, `name: ${state1.name}`)

}

})Although we haven't implemented watch in this chapter yet, it is written here for the sake of illustration.

In this component, the targetMap will eventually be formed as follows.

The key of targetMap is "a certain target". In this example, state1 and state2 correspond to that.

The keys that these targets have become the keys of targetMap.

The effects associated with them become the values.

In the part () => h("p", {}, name: ${state1.name}), the mapping state1->name->updateComponentFn is registered, and in the part watch(() => state2.count, onCountUpdated), the mapping state2->count->onCountUpdated is registered.

This basic structure is responsible for the rest, and then we think about how to create (register) targetMap and how to execute the effect.

targetMap is a notebook that records "who affects whom".

When state1.name changes → run updateComponent

When state2.count changes → run onCountUpdated

It records these relationships!

That's where the concepts of track and trigger come in. As the names suggest, track is a function that registers in targetMap, and trigger is a function that retrieves the effect from targetMap and executes it.

export function track(target: object, key: unknown) {

// ..

}

export function trigger(target: object, key?: unknown) {

// ..

}And these track and trigger are implemented in the get and set handlers of Proxy.

const state = new Proxy(

{ count: 1 },

{

get(target, key, receiver) {

track(target, key)

return target[key]

},

set(target, key, value, receiver) {

target[key] = value

trigger(target, key)

return true

},

},

)The API for generating this Proxy is the reactive function.

function reactive<T>(target: T) {

return new Proxy(target, {

get(target, key, receiver) {

track(target, key)

return target[key]

},

set(target, key, value, receiver) {

target[key] = value

trigger(target, key)

return true

},

})

}

- track: Called when "reading" a value, registers "run X when this value changes"

- trigger: Called when "writing" a value, executes registered handlers

- reactive: A function that creates a Proxy with this mechanism

Here, you may notice one missing element. That is, "which function to register in track?". The answer is the concept of activeEffect. This is also defined as a global variable in this module, just like targetMap, and is set in the run method of ReactiveEffect.

let activeEffect: ReactiveEffect | undefined

class ReactiveEffect {

constructor(

// here, you give the function you want to actually apply as an effect (in this case, updateComponent)

public fn: () => T,

) {}

run() {

activeEffect = this

return this.fn()

}

}To understand how it works, imagine a component like this.

{

setup() {

const state = reactive({ count: 0 });

const increment = () => state.count++;

return function render() {

return h("div", { id: "my-app" }, [

h("p", {}, [`count: ${state.count}`]),

h(

"button",

{

onClick: increment,

},

["increment"]

),

]);

};

},

}Internally, this is how reactivity is formed.

// Implementation inside chibivue

const app: App = {

mount(rootContainer: HostElement) {

const componentRender = rootComponent.setup!()

const updateComponent = () => {

const vnode = componentRender()

render(vnode, rootContainer)

}

const effect = new ReactiveEffect(updateComponent)

effect.run()

},

}To explain step by step, first, the setup function is executed.

A reactive proxy is generated at this point. In other words, any operation performed on the proxy created here will behave as configured in the proxy.

const state = reactive({ count: 0 }) // Generating a proxyNext, we pass updateComponent to create a ReactiveEffect (Observer side).

const effect = new ReactiveEffect(updateComponent)The componentRender used in updateComponent is a function that is the return value of setup, and this function references the object created by the proxy.

function render() {

return h('div', { id: 'my-app' }, [

h('p', {}, [`count: ${state.count}`]), // Referencing the object created by the proxy

h(

'button',

{

onClick: increment,

},

['increment'],

),

])

}When this function is actually executed, the getter function of state.count is executed, and track is triggered. In this situation, let's execute the effect.

effect.run()Then, updateComponent (a ReactiveEffect with updateComponent) is set to activeEffect. When track is triggered in this state, a map of state.count and updateComponent (a ReactiveEffect with updateComponent) is registered in targetMap. This is how reactivity is formed.

Now, let's consider what happens when increment is executed. Since increment is rewriting state.count, the setter is executed, and trigger is triggered. trigger finds and executes the effect (in this case, updateComponent) from targetMap based on state and count. This is how the screen update is triggered!

This allows us to achieve reactivity.

It's a bit complicated, so let's summarize it in a diagram.

Based on these, let's implement it.

The most difficult part is understanding everything up to this point, so once you understand it, all you have to do is write the source code. However, even if you understand only the above, there may be some people who cannot understand it without knowing what is actually happening. For those people, let's try implementing it here first. Then, while reading the actual code, please refer back to the previous section!

First, let's create the necessary files. We will create them in packages/reactivity. Here, we will try to be conscious of the configuration of the original Vue as much as possible.

pwd # ~

mkdir packages/reactivity

touch packages/reactivity/index.ts

touch packages/reactivity/dep.ts

touch packages/reactivity/effect.ts

touch packages/reactivity/reactive.ts

touch packages/reactivity/baseHandler.tsAs usual, index.ts just exports, so I won't explain it in detail. Export what you want to use from the reactivity external package here.

Next is dep.ts.

import { type ReactiveEffect } from './effect'

export type Dep = Set<ReactiveEffect>

export const createDep = (effects?: ReactiveEffect[]): Dep => {

const dep: Dep = new Set<ReactiveEffect>(effects)

return dep

}There is no definition of effect yet, but we will implement it later, so it's okay.

Next is effect.ts.

import { Dep, createDep } from './dep'

type KeyToDepMap = Map<any, Dep>

const targetMap = new WeakMap<any, KeyToDepMap>()

export let activeEffect: ReactiveEffect | undefined

export class ReactiveEffect<T = any> {

constructor(public fn: () => T) {}

run() {

// ※ Save the activeEffect before executing fn and restore it after execution.

// If you don't do this, it will be overwritten one after another and behave unexpectedly. (Let's restore it to its original state when you're done)

let parent: ReactiveEffect | undefined = activeEffect

activeEffect = this

const res = this.fn()

activeEffect = parent

return res

}

}

export function track(target: object, key: unknown) {

let depsMap = targetMap.get(target)

if (!depsMap) {

targetMap.set(target, (depsMap = new Map()))

}

let dep = depsMap.get(key)

if (!dep) {

depsMap.set(key, (dep = createDep()))

}

if (activeEffect) {

dep.add(activeEffect)

}

}

export function trigger(target: object, key?: unknown) {

const depsMap = targetMap.get(target)

if (!depsMap) return

const dep = depsMap.get(key)

if (dep) {

const effects = [...dep]

for (const effect of effects) {

effect.run()

}

}

}I haven't explained the contents of track and trigger so far, but they simply register and retrieve from targetMap and execute them, so please try to read them carefully.

Next is baseHandler.ts. Here, we define the handler for the reactive proxy. Well, you can implement it directly in reactive, but I followed the original Vue because it is like this. In reality, there are various proxies such as readonly and shallow, so the idea is to implement the handlers for those proxies here. (We won't do it this time, though)

import { track, trigger } from './effect'

import { reactive } from './reactive'

export const mutableHandlers: ProxyHandler<object> = {

get(target: object, key: string | symbol, receiver: object) {

track(target, key)

const res = Reflect.get(target, key, receiver)

// If it is an object, make it reactive (this allows nested objects to be reactive as well).

if (res !== null && typeof res === 'object') {

return reactive(res)

}

return res

},

set(target: object, key: string | symbol, value: unknown, receiver: object) {

let oldValue = (target as any)[key]

Reflect.set(target, key, value, receiver)

// check if the value has changed

if (hasChanged(value, oldValue)) {

trigger(target, key)

}

return true

},

}

const hasChanged = (value: any, oldValue: any): boolean =>

!Object.is(value, oldValue)Here, Reflect appears, which is similar to Proxy, but while Proxy is for writing meta settings for objects, Reflect is for performing operations on existing objects. Both Proxy and Reflect are APIs for meta programming related to objects in the JS engine, and they allow you to perform meta operations compared to using objects normally. You can execute functions that change the object, execute functions that read the object, and check if a key exists, and perform various meta operations. For now, it's okay to understand that Proxy is for meta settings at the stage of creating an object, and Reflect is for meta operations on existing objects.

Next is reactive.ts.

import { mutableHandlers } from './baseHandler'

export function reactive<T extends object>(target: T): T {

const proxy = new Proxy(target, mutableHandlers)

return proxy as T

}Now that the implementation of reactive is complete, let's try using them when mounting. ~/packages/runtime-core/apiCreateApp.ts.

import { ReactiveEffect } from '../reactivity'

export function createAppAPI<HostElement>(

render: RootRenderFunction<HostElement>,

): CreateAppFunction<HostElement> {

return function createApp(rootComponent) {

const app: App = {

mount(rootContainer: HostElement) {

const componentRender = rootComponent.setup!()

const updateComponent = () => {

const vnode = componentRender()

render(vnode, rootContainer)

}

// From here

const effect = new ReactiveEffect(updateComponent)

effect.run()

// To here

},

}

return app

}

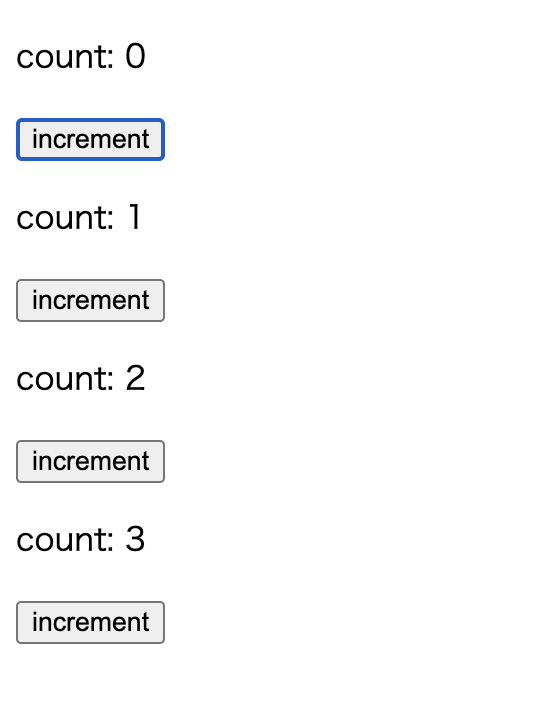

}Now, let's try it in the playground.

import { createApp, h, reactive } from 'chibivue'

const app = createApp({

setup() {

const state = reactive({ count: 0 })

const increment = () => {

state.count++

}

return function render() {

return h('div', { id: 'my-app' }, [

h('p', {}, [`count: ${state.count}`]),

h('button', { onClick: increment }, ['increment']),

])

}

},

})

app.mount('#app')Oops...

The rendering is working fine now, but something seems off. Well, it's not surprising because in updateComponent, we create elements every time. So, let's remove all the elements before each rendering.

Modify the render function in ~/packages/runtime-core/renderer.ts like this:

const render: RootRenderFunction = (vnode, container) => {

while (container.firstChild) container.removeChild(container.firstChild) // Add code to remove all elements

const el = renderVNode(vnode)

hostInsert(el, container)

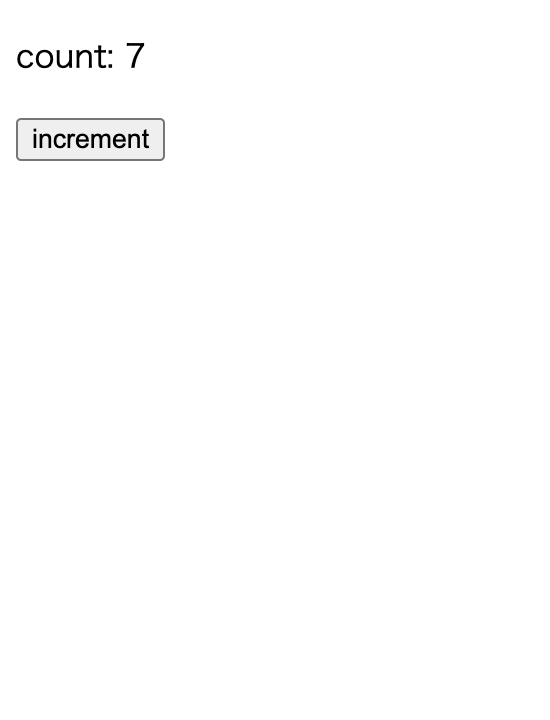

}Now, how about this?

Now it seems to be working fine!

Now we can update the screen with reactive!

The basics of the Reactivity System are complete!

Do you understand the secret behind Vue.js's "magic" of automatic screen updates?

By overcoming this, you now have a deep understanding of Vue.js internals!

Source code up to this point: GitHub